Kevin Spacey – Clarence Darrow :: Old Vic Theatre, London :: 4-6-2014

Photo Credit: Manuel Harlan for The Guardian

“I am pleading for the future… when hatred and cruelty will not control our hearts, when we can learn that all life is worth saving; that mercy is the highest attribute of man.”

For an actor, assuming you’re not one of the out-of-work ones (rare itself), there’s a certain career path that has been well-trodden over the last half century, since the end of the studio system and the exclusivity contracts given to their stables of stars. The early fight for supporting roles, the toil through endless auditions, catching the eye in average movies, which lets you move onto the next rung, then perhaps getting a decent agent, and then even more supporting roles but maybe in better movies. Depending on what you look like, you could make it to the part of the best friend or love interest, though it would actually be better to be unusual or even average looking, because only then might the parts get interesting. Perhaps you’ll pull the supporting role of a lifetime, the unlikely hero or the revealed villain, and steal the movie. You can succeed because it’s been pre-decided, due to your non-Jackman/Pitt/Cruise level looks, that you’re not the leading man, but you’re eye-catching enough to form important connections with people who’ll stand up for you when the studio wants someone more traditionally handsome for their next Oscar-bait drama: the kind that Hollywood used to make, until fairly recently. This path was largely unaltered until around fifteen years ago, when a shift started to happen in the mainstream movie business. The Hollywood paymasters shoved real creatives toward the margins and even the smaller movies started to be made by committee. The approach itself wasn’t new but the players were. Marketing executives with an eye on toy markets, merchandising, one-sheets, TV spots and sequels were now sending notes back on scripts – these people had not a clue on earth what components a film needed to be good. They used to come in after a movie was made, with no part played in the creative process, but it all changed and getting great writing onto the big screen suddenly became as easy as pushing water up a hill.

Disillusioned creatives saw this commerce, rather than arts, driven approach becoming the new normal and started to do something drastic and unprecedented – they moved to TV. Before, TV had been the last refuge of the failed movie actor. There’s a lot to be said for a steady paycheck. The first stirrings were seen as the century ended, with the 1999 premieres of both The West Wing on broadcast (the channels everyone gets) and The Sopranos on cable, (which you pay for, in the US model). Bit by bit, the best actors started dropping out of movies and into TV, because that’s where the great dramas were now being made. They ran away from the comic book adaptations, the tent-pole summer blockbusters and the sequels, perhaps indulging in a little voice acting for animations to top up the bank balance. Some rushed straight into TV, while others rushed straight to the stage. A few were clever enough to do everything: take a good part in a small movie for a nice wage when the script was good enough, focus on theatre and help to get plays on not just by starring in them but by producing them, and finally, only when the absolutely perfect part came along, created by none of the established cable networks (operating outside even HBO/AMC/Showtime et al. without any constraints, the newest players are Netflix, Hulu and Amazon: with no track record comes no fear, nor limits on adventure or investment), jump on it and create a career where half the year is spent doing a remarkable TV show and the other half is spent with theatre sawdust in the nostrils. This is how to conduct a career, be in charge of it, while taking or creating the best opportunities. And thus, we come to Kevin Spacey.

Put simply, eleven years ago he opted out of Hollywood, at a time when his star was sky high and $10m a movie was on the table. He saw that great movie drama was in trouble but wasn’t quite ready to be on the small screen. So he moved to London and became the artistic director of the Old Vic Theatre in Waterloo. Many thought this was some vanity project. A chance to use his name to act in a series of revivals and just get as many eyeballs on him as possible. That may be the perception, but the facts don’t bear it out: since 2003, he has directed only two plays and starred in seven (his last being 2011’s acclaimed Richard III, which saw a reunion with Sam Mendes), but has shepherded over forty onto the stage, by focusing his not inconsiderable reserves of personal charm onto fundraising and creative partnerships. While the Old Vic, at nearly 200 years of age, wasn’t quite the busted flush that some of the media suggested pre-Spacey’s arrival, he has turned it into a theatre that can attract the newest and most exciting plays, to rival the National Theatre (which once controlled it). His aim was not just to reinvigorate the place, but also to create a structure and innovative ethos that would allow it to continue long after he abdicated. Next year he will hand over to Matthew Warchus, whose credentials catch the eye; most recently, he directed the magical Matilda musical, which won seven Oliviers and five Tonys last year.

Darrow has been called a civil rights lawyer, but this is an oversimplification. He defended murderers threatened with the death penalty to prevent the state from committing another display of dehumanising horror themselves, arguing that mercy is what makes society better, and how revenge will only make us harder people. He proudly saved 102 people from death row. Humanity’s good aims interested him more than America’s often Biblically inspired desire for revenge; he believed in trying to pry out people’s innate goodness. But more than this, his philosophy was to fight for the common man and woman. A full forty years before the turning point of the civil rights battle he lined up behind black defendants faced with all-white juries. The most celebrated case of this type was that of Ossian Sweet, a black doctor who had the temerity to move into a white neighbourhood. His home was surrounded by an angry mob and, as they advanced to his door, a shot was fired that killed one of the invaders. In many US states this would be allowed under the so-called ‘stand your ground’ law, sadly now used to free killers like George Zimmerman. Darrow defended Sweet and, in a landmark case, he was acquitted of murder.

The text of the play itself, written by David W. Rintels (based on the biography Clarence Darrow For The Defense by Irving Stone, who also wrote the famed van Gogh bio Lust For Life) and first performed by Henry Fonda in 1974, is fairly straightforward. It’s an autobiographical run through of Darrow’s most famed cases, after first illuminating his Ohio upbringing, to freethinking parents: his mother talked of suffrage in 1840, no less than 80 years before women gained countrywide voting rights. It briefly covers his move to Chicago, his first marriage, and even a little of the unfounded jury bribery allegations that beset him during the case of the McNamara brothers, who had planted a bomb in the offices of the Los Angeles Times during a labour union dispute: not intending to harm anyone, they had killed 21 newspaper employees; Darrow saved them from the noose. He defended Pennsylvania miners, who were working fourteen hours a day, 365 days a year, against their bosses, arguing for better pay and working conditions. Spacey made the audience gasp with a tale of an 11-year-old child miner who had a leg amputated due to employer negligence: he was manipulative in the way that all great arguers are. A champion of the unions, no doubt the right-wing would today call him a Communist. He never even claimed to be a socialist; he was simply a man who wanted to use his intellect and talents to stand up for the underdog. He was an inspiration to anyone who wants to speak for the vulnerable. He didn’t mind a bit of media-bait either, perhaps best encapsulated in the Scopes ‘monkey’ trial, following a schoolteacher’s prosecution for teaching evolution in the Bible Belt. The play finishes, inevitably, to a coruscating powerhouse denouement on perhaps Darrow’s most famous case, that of Leopold and Loeb, two rich teenagers who killed a 14-year-old boy merely for the experience and excitement, the challenge of getting away with it. This is where the concept of mercy came in, as Darrow fervently believed that we can only move forward as a collective culture when we reject the baser instincts of our human nature. He believed without pause in rehabilitation over retribution as a model for how a civilised society should behave.

Spacey had played Darrow no less than twice before. When pressed, he has said that the first occasion, a 1991 low budget PBS movie, was his favourite filming experience. The second time was in a 2009 Old Vic production of Inherit The Wind, (with the Darrow character alternately named Henry Drummond). He is the fourth fine actor to play the role: after Fonda, Orson Welles took him on in 1959’s Compulsion, a thinly fictionalised account of the Leopold and Loeb trial; perhaps the most famous incarnation was in the film adaptation of Inherit The Wind, with Spencer Tracy’s Oscar nominated version taking the plaudits.

A one-man (or woman) show is not to be trifled with, and few actors on earth could hold the rapt attention of a thousand people the way Spacey does. Once I got over the initial thrill of seeing such a renowned actor in person, and only a few feet away, it was an easy pleasure to get swept away in the invective and the complete command and control he has over an audience. It’s not just his level of stagecraft and experience, which is considerable (I’d seen him once before, unashamedly scene-stealing in The Philadelphia Story in this same venue) – it’s the sheer force of his charismatic presence. This is an actor at his absolute career peak, both in person and on screen. In his other job, House of Cards, he gives you barely a drip of humanity, and yet still you root for his Machiavellian politician. Such is his skill that he can strip away any remaining vestige of humanity, as in Se7en, and leave you disgusted but in awe. He can project a seductive quality, as in LA Confidential, or pathetic desperation, as in American Beauty. He can scenery-chew for a giggle, as in the otherwise unwatchable Superman Returns, or con you completely, in The Usual Suspects. He even stood up to his mentor Jack Lemmon, perhaps the actor he resembles the most in the cinema canon, in Glengarry Glen Ross. During the second half, I heard an anachronistic noise: it became clear that a mobile phone was going off (idiots are present everywhere) and, in character, without breaking a beat, he said ‘If you don’t answer that, I will.’ Everything appears to be effortless, which is as it should be when you work as hard as Spacey does.

Perhaps the only cautionary tale is that we should now be able to view Darrow’s humanitarianism as quaint, a relic of a more closed-minded century. Unfortunately, the world is no less right-wing (it just seems like it is because we talk more; activism is higher but pushback is greater) than it was during his heyday. While some progress has been made, governments are more secretive and still as keen to crush uprisings (for example, in the last year 40,000 protestors have been jailed in Egypt, with all forms of protest now banned by a government elected as a result of protests), while citizens are more suspicious, and rightly so given the inroads made on liberties and how much we are spied on daily. The game is rigged, with little advances made in social justice and minority interest groups dominating the conversation (belief in climate change is crazy and anti-business while belief in invisible gods is sky high). What is the internet itself, except a method from which data is collected on behaviours, and how long before it’s yanked under corporate control and net neutrality becomes a thing of the past? Most of the jail populations still come from backgrounds of poverty and poor education, while education funding itself is slashed and healthcare is sold to the highest bidder. He should be a winner on the right side of history, not an anomaly pushing against the tide. A century later, we need fighters like Darrow more than ever.

...

Crosby, Stills and Nash :: Royal Albert Hall, London, 8-10-13/9-10-13

And so the splits went down like this: Graham Nash, from Salford, Manchester (though born in Blackpool), wrote a jaunty tune called Marrakesh Express and his band, The Hollies, hated it, which started off the trouble. I had always, somewhat unfairly, teased that Nash was a little Ringo-ish: a guy with the perfect personality who just fitted in with the more talented ones. I do find him a little cheesy, I admit, with his mid-Atlantic accent, but he’s a brilliant songwriter, with a lovely voice, and he’s even got a creditable second career, having been a digital art pioneer in the early 80s, as a rather excellent photographer. This is the man Joni wrote Blue about. There must be more to him.

David Crosby is truly one of my favourite people on earth. I met him once, at a solo show at the Jazz Café. I’d seen his former bandmate Roger McGuinn there earlier that same year, and though I’m not an autograph person, I happened to have pinched my parents’ Byrds box set and took the booklet along. Management gofers took handfuls of memorabilia, returning with signatures. McGuinn, well known as not being the nicest guy, refused to meet anyone. Crosby, on the other hand, held court in the bar upstairs, talking warmly with everyone, signing everything proffered at him. I have no recollection of my fangirl babble, but I do remember that he looked at me with the kindest face I’d ever seen, his big cheeks puffing out as he smiled, framing his magnificent white handlebar moustache. It’s what God, if he existed, should look like.

As he started to move away from the volcanic troubles in The Byrds, he found himself delving further into a hippy ideal and nowhere was that purer than, not Woodstock, at 1967’s Monterey Pop Festival. Of all of the landmark rock festivals, and there were plenty, that one, for me, is the standout. It had the best bill, the best atmosphere, no trouble, no lack of facilities and a manageable medium-sized 60,000 strong crowd (though the performance spaces only held 8,000 each, so most missed the bands; everyone was there for the vibe, man). Gene Clark had already left The Byrds by then, driven out by the stress of dealing with everyone else, McGuinn and Chris Hillman in particular. During their appearance, Crosby went off, ranting about Vietnam, and then further annoyed his bandmates by stepping in for an absent Neil Young to guest with Buffalo Springfield, at their leader Stephen Stills’ request. The cracks were there and, as these things go, it all happened pretty fast. Stephen and Graham quit, and David was fired. The three met for the first time at David’s house on one sunny Laurel Canyon day in 1968, and sang together for the first time.

Famously, Woodstock was only the second Crosby, Stills and Nash show. Neil Young, who did play with them briefly there but was too nervous to be filmed, had also jumped the Springfield ship and, of course, has been in and out of the band for many decades. But for me, it's all about the core three. The spikiness of Stills, who knows he’s the leader only when Neil’s absent, and the brotherly Crosby and Nash, who’ve made great duo records and often tour together. I’d seen them live at Glastonbury in 2009, though my overall experience that year wasn’t positive, and I remember little of their performance anyway. I got a last minute ticket from a woman called Barbara; after my failure to get Fleetwood Mac tickets the other week, it felt like I was meant to be there.

However much I thought I'd enjoy this concert, it completely exceeded my expectations. It was a 3-hour odyssey through some of the best songwriting of the last half-century. Crosby is now 72, Stills is 68 and Nash is 71. It’s dull to talk about ageing rock stars. There are no ageing painters or playwrights. There’s no need to be shocked when, despite grey hair and slightly wider waistbands, a band like this are in great shape. It’s what they do, what they’ve always done. They’re touring, hardened musicians who have been playing live for almost 50 years. Their energy does not flag, while new songs are numerous and hit the mark. ‘These new songs stop us from being The Eagles’, Graham quipped. One must admire their bullish insistence on playing several new compositions every night; as we know, many of their contemporaries don’t bother, either because of fear of clearing the venue or because the creative wellspring ran dry long ago. Nobody leaves for a loo/pint break during these new songs, like you usually see at gigs like this. And by ‘like this’ I mean the nonsensical concept of oldie or nostalgia acts. Get on, play the hits, the tickets are expensive, I want to get home before 11, the crowd think. A venue’s size at this level can, I think, influence the setlist, the choices made. At the Royal Albert Hall, which seats a crowd of around 4500, there was an undeniable emotional intimacy. Playing in a ‘small’ venue (as opposed to, say Wembley Arena or the O2) lets them indulge themselves a little more, maybe playing a more varied setlist. Perhaps it felt so intimate because I had seats on the surprisingly cosy floor. They made it feel like a living room.

This band have survived it all. Coked-up 70s madness, death (Crosby’s girlfriend Christine Hinton was killed in a car accident, which it’s been said he’s never recovered from, though he has been evened out by Jan, his wife of 36 years), fighting (you sense Neil vs. Stephen was the main attraction), a couple of overdoses (Stills, in the 70s), and yet they kept getting drawn back together. From the opening chords of Carry On , from 1970’s Déjà Vu, this was such a special night. Those three voices soared, backed ably by a brilliant band: Todd Caldwell, organ; Shane Fontayne, guitar; Steve DiStanislao, drums (superb!); Kevin McCormick, bass, and James Raymond (Crosby’s son) on keyboards.

There’s something about the beauty of vocal harmonies at this level (there’s little, Beach Boys aside, this good) that always gets me. In particular, David and Graham’s voices ache with exquisite sympatico. The tempo never dropped, incredible pop songs just kept on coming: Almost Cut My Hair (a Crosby tour-de-force), Buffalo Springfield song Bluebird, performed without C&N, which brought a rapturous ovation following fiery guitar work, Long Time Gone (used in the opening scene of Woodstock of course), the perfect pop of Nash’s Military Madness, it was endless. Cathedral was prefaced by his tale of its creation, “One day I decided to get up really early, take acid, rent a Rolls Royce, and go to Stonehenge. In those days you could touch the stones. I lay on the ground for a thousand years, or it could have been 10 seconds, I couldn’t tell. I walked to Winchester Cathedral, and found myself chilled to the bone as I stood on the grave of a soldier who had died in 1799, but on my birthday.” The RAH’s newly restored pipe organ was bathed in red light and its tones filled the room (though it was begging for a Spinal Tap papier-mâché model to descend). Before the sweet tale of domesticity that is Our House (which has had a second life as an accompaniment to various TV adverts), he started off by talking about Joni. One day they went out shopping and she saw this nice little vase, which he encouraged her to buy. When they got home, he said ‘I’ll light the fire, you put the flowers in the vase that you bought today.” The crowd broke into warm applause, recognising that simple post-shopping trip sentence as the first lyric couplet.

It went on: Helplessly Hoping, and its perfect harmonies, brought tears to the eyes, Crosby’s signature love song Guinnevere, Déjà Vu, Southern Cross, the magnificent Wooden Ships and, of course, Suite: Judy Blue Eyes. New songs and old, mountains of charm and passion, the kind of togetherness you feel lucky to witness, from men who’ve been through everything together, through rain and shine. I was overcome, by history, songwriting, guitar playing that’s hardly done like that anymore, and that sweet trio of voices. Unforgettable night. Graham’s hometown show in Manchester happens on Saturday, I envy my dad that he’ll see this remarkable band (for the first time: he’s seen solo Stills, CSNY and C&N, but never just all three).

_______________________________

I’ve just made an offer on Scarlet Mist for a ticket for tonight’s show. Bonkers, you may say, but if a chance is in front of you, take it without regret.

Incidentally, it seems to be considered odd to see multiple gigs on one tour. Few understand why I’ve done it so often. It’s normal to see the same band a year apart, on the next tour, but strange to see them a day apart? In all honesty, I haven’t felt like this for 18 months. I’ve enjoyed the gigs I’ve attended, but last night felt like something old was coming back, some spark of joy in myself that had been lost. It’s a tiny step, but nevertheless, it feels very real. That’s why I’m going again. More to come…

___________________________________

So, the second show. An even better seat this time, giving me a new angle, letting me see details previously invisible. Graham Nash performs barefoot, who knew? The stage is festooned with rugs and a couple of scarves. The interplay is much clearer second time around. You can still see, even now, the divisions between Stills and the others. I wonder if he’s jealous of their brotherhood? Maybe. I do think he’s bemused and annoyed by not being Neil Young. You get the sense he can’t believe he’s not playing arenas by himself whereas the other two don’t care at all, they’re just happy to be performing. A passage in Nash’s autobiography sums up the differing vibes, the personalities, of his bandmates: “I had never met anybody like Crosby. He was an irreverent, funny, brilliant hedonist who had been thrown out of The Byrds the previous year. He always had the best drugs, the most beautiful women, and they were always naked. Stephen was a guy in a similar mould. He was brash, egotistical, opinionated, provocative, volatile, temperamental, and so talented. A very complex cat, and a little crazy.”

Graham, though it pains me to praise a United fan, is very charming. Joni’s famous quote about free love (what bullshit it was, how it was only good for men) was, I suspect, said with him in mind. She’s the one that got away, certainly, but his wandering eye paid to that, though initially she had tracked him down and seduced him. You constantly hear ‘hey, it was the 60s/70s!’ to excuse a lot of misogynist behaviour. Not that times and the perception of morals weren’t different then. Joni had had a brief fling with Crosby, who wasn’t the possessive type and was cool when she invited Graham to live with her on his first day in LA. Indeed, he later shared one of his other girlfriends with Nash, who stole Rita Coolidge from Stills, who had a long relationship with Judy Collins and so on and on. But the machinations and treatment of women in the 1970s is a subject for another day…

I enjoyed the second gig just as much as the first, undoubtedly. It was another intimate, emotional night, which made the venue seem small. It was fun, as it always is, to watch middle-aged, middle-class, white people try to let go. A foot tap, a head bob, polite applause for Stills’ guitar virtuosity… English people are so tightly wound sometimes. Particular treats were To The Last Whale, from Wind On The Water, Crosby & Nash’s 2nd album, and a magnificent version of Triad, David’s odd yet sweet invocation of the benefits of threesomes. He’d written it during his time in The Byrds but McGuinn rejected it, horrified. Jefferson Airplane were not so squeamish and took it on, covering it on their album Crown Of Creation. Again, the S-only (no C&N) version of Buffalo Springfield’s Bluebird just blew me away. I closed my eyes and, during the free psychedelic blues jam freakout of its second half, was simply transported to another place entirely.

It’s hard to put your finger on what keeps this band together, given their histories of bickering and drug trouble. I can only surmise that it’s just pure chemistry, the non-narcotic kind, because when you watch them live it’s a magical experience. They know it, from first note to last: that they are greater together than apart. It’s all about those hugely different voices. The high notes left Stephen long ago, but a gravelly tone serves him so well, despite the odd note missed. Amazingly, Graham can still sing in a nicely high register, which is particularly welcome and surprising. Perhaps David’s voice is the strongest individually, which considering he’s been through decades of drug addiction, culminating most spectacularly in a spell in prison in the early 80s, almost feels shocking. It’s like watching Keith Richards’ gnarled, deformed, arthritic hands play a perfect solo during Sympathy For The Devil. It makes no sense but there it is, your eyes and ears don’t lie. He’s got the same childlike joy as Keith has; he’s a survivor who’s just happy, and genuinely surprised, to be alive. The harmonies might not hit the same high notes they used to but during Helplessly Hoping it was like time stood still, I’ve never heard voices so sweet. Even in lower tones, it was remarkable to witness. As the band left the stage and I took a deep happy breath, the tannoy led the crowd out with refrains of We’ll Meet Again. I hope so.

Carry On/Questions (CSNY)

Pre-Road Downs

Long Time Gone

Just a Song Before I Go

Southern Cross

Marrakesh Express (night 1 only)

Lay Me Down (C&N)

Military Madness (night 1 only)

Time I Have

Cathedral

Bluebird (Buffalo Springfield)

Déjà Vu (CSNY)

49 Bye-Byes

Set 2

Helplessly Hoping

Teach Your Children (CSNY)

Treetop Flyer (Stephen Stills song)

Golden Days (2nd night only)

What Are Their Names

Guinnevere

Burning for the Buddha

Triad (Jefferson Airplane cover)

Critical Mass/Wind On The Water (2nd night only)

Our House

Almost Cut My Hair (CSNY)

Wooden Ships

Encore:

Suite: Judy Blue Eyes

_____________________________

Addendum:

Dad’s report – amazing, emotional show. Judy Blue Eyes was not played (they ran over the curfew I suspect). Graham dedicated a song to his sister and her family, who were present. David said ‘I have so much to thank Manchester for; you gave me my best friend in life.’

Dad wanted to add to this the story of how he ignored Joni Mitchell. In early 1970 he was working in Burtons, a men’s clothes store on Deansgate in Manchester. A crowd of four came in and he immediately recognised one as Graham Nash. He ran up to him and engaged him in conversation, and they chatted for a while. He told Graham he’d just bought the first Santana album and loved it, to which Graham replied that they’d just played a gig with them in New York. They talked about music, and Graham bought a sheepskin coat for his step-dad. What a trip, right? A few weeks later a colleague said ‘wasn’t that amazing, when he came in with Joni Mitchell’. The blood drained from dad’s face.

The three women had been Graham’s mother, sister and girlfriend. He had ignored her completely, so wrapped up was he in talking music. He later wrote to MOJO, apologising to Joni for ignoring her, as she was the love of his life, adding ‘don’t worry, my wife knows about that!’

...

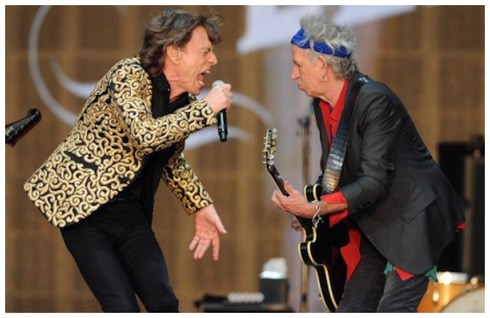

The Rolling Stones :: Hyde Park, London, 13-7-13

The Rolling Stones are unreviewable. There is no element of surprise with a live show like theirs: you know what you’re going to get. The only surprise comes from your own muscle memory, how these songs are part of your heart and brain, how you instinctively know every note and word. For me anyway, they trace the line of so much, including my relationship with my mother, who was trying to get me into Mick when she showed me the video for Dancing In The Street. She finally got me in 1990 when we watched the VHS of 25x5 until the tape was worn out. We saw them live on August 25th 1990 at Wembley Stadium – she would always tease me and say ‘you said Keith looked straight at you!’ Hey, I was 13, we were quite near the front, and I coulda sworn he had. They were her favourite band: they were our band. More than her other faves like Miles, Bob or even the Beatles – the Stones belonged to us.

I hadn’t seen them live since we saw them again in Sheffield in 1995 – they’ve toured several times since but I always said ‘they’ve had enough of my money’. When they announced a return to Hyde Park, for the first time since the concert they had played there following the death of Brian Jones, I did raise an eyebrow but it fell on the night of a Bowie party long in the planning. But then, when they announced a show the week after, it felt like I was meant to be there – following in mum’s footsteps, she had attended the 1969 show. When I got lucky with tickets, it was on.

Concert-going, in the pop/rock arena, is split into sections – young artists, who plough their debut albums in small venues; the mid-level bands on albums 3 or 4 doing the same in slightly larger, say Roundhouse-size, places, who throw in well-received tracks from their previous records. There’s your established acts, say aged between 30-45, who are probably big enough to play an arena but prefer a run of gigs at a theatre. The audience care about the new record but the band knows there’s a balance to be found. Then there’s that hideous phrase, the heritage act. With the notable exceptions of Neil Young, Robert Plant, Bruce Springsteen and a few others, new stuff is neither played nor wanted. A nostalgia party takes place. There’s a couple who don’t tour at all, like Bowie and Joni, but that’s rare, most want to fill an arena and relive their glory days. At the older end of even that scale the Stones stand alone – they don’t much care about new material, and neither does anybody else. They wouldn’t, they couldn’t, do a version of The Next Day; adding to the musical canon matters not. It’s about leaving something behind that people can actually see. It’s about the experience of being in their presence. The notion of retirement has always been a stupid question, for a different day. The blues guys they worship went on into their 80s (partly because they were ripped off and had to but that’s yet another issue) and nobody suggests that actors or painters or musicians playing jazz or classical music give it all up when they’re over 60. Pop music is certainly a young person’s game but if you can still deliver, why the fuck shouldn’t you? I watched what was allowed to be televised at Glastonbury the other week. They hit some high spots but honestly, it wasn’t great. However, many bands try and fail at that level, where you’re piloting into someone else’s stage, sound system, technicians, cameras etc. U2 fell a little flat when they headlined too, though to be fair to them that was more to do with torrential rain turning the stage into an ice rink, rendering them static and nervous. I’d seen a few clips of the O2 shows they did at the end of last year, and those were better. As such, at this level, and given the famed level of control Mick loves, when they’re on their own turf everything tends to come together.

Having said that, they are not, and have never been, polished. They don’t churn out perfect Fleetwood Mac style MOR and they don’t play note-perfect recreations a la Pink Floyd. Stay at home and listen to the records, if that’s what you want. They are a bit ramshackle, it could all fall to bits, there’s the odd bum note, but this is a band with Keith Richards in it after all, and he is the musical leader, so that can’t bother you. If it does, you don’t know your Stones history very well. Their shows might not offer the danger of yore, and their (or at least Mick and Charlie’s) approach might be super-professional, but you can still let go and see the sparks between them. They’re breaking this mould – there are no other rock bands who’ve been together for 50 years. Think about that time frame, think about how many generations have come and gone, how many challengers they’ve seen off. They’re not flawless, they’re a little bit dirty and messy, and that’s why I’ve loved them so much for nearly 25 years.

It was a beautiful, blue-skied day, and we sat in the sun for a few hours before the quite enjoyable Jake Bugg came on. He’s pretty great for a teenager. We’d smuggled rum into the venue in the back of our trousers (it’s not my first time) and this turned out to be a wise move. A few bottles of mixers were procured and we were set for the evening, having found a great spot by one of the screens. The pre-show warm-up tape was a bit of blues, as you’d expect, but then on came Milestones, the 1958 classic by Miles Davis. A second later a woman wearing a Star of David walked past me. It might sound like I’m full of shit but I had a little moment where I felt like my mum was right there. The show started with a brief film of the original Hyde Park show, right on time, on the dot of 8.25pm. Start Me Up! Then It’s Only Rock And Roll, and then Tumbling Dice. Big punches, thrown one after the other, they’ve got songs to burn. The energy and noise level started to rise and, despite it being the hottest day of the year, stayed sky high for the next 2 hours. It was a pleasure to hear the languid disco funk of Emotional Rescue, a bit of a surprise (played for the first time ever 2 months ago, this was its first European performance, amazingly), and I couldn’t help but smile as Mick’s perfect falsetto rang out across the grass. It’s a ridiculous song, a daft attempt at being on-trend in the Studio 54 era, but it also feels like an old friend.

The backing players are staples now themselves – bassist Darryl Jones, who has been playing with them for two decades, impressed hugely, and nobody gave a thought to the old Bill. Backing vocalists Lisa Fischer (incredible on Gimme Shelter) and Bernard Edwards, in their 25th year of touring with the band, are beautifully settled and woven in. Chuck Leavell, a Stones veteran of some 31 years, adds boogie-woogie piano that Ian Stewart would have been proud of. And of course, the tough Texan warhorse Bobby Keys has been playing sax with these old boys longer than Ronnie’s been in the band (on and off from 1970-81 but a constant from ’82 onwards). Mick Taylor had been asked to join in June ’69 after Brian was fired and, less than a month later, two days after Brian died, he was making his stage debut. Arguably, he’s the best guitarist that’s ever played with them, and certainly their highest creative points were reached in his years with the band (1969-75). He has been playing with them on this tour and, though I knew it was coming, what a pleasure it was to hear him play on a mindblowing version of my favourite live Stones song Midnight Rambler (pleasingly, he made another bow in Satisfaction, at the end).

Charlie is of course solidity personified, even if you know he’d rather be at Ronnie Scott’s playing some Art Blakey licks. It’s charming that he’s still so thoroughly unimpressed by the machinery of the rock music industry all these years later. He likes to complain about being in this band, but he always answers Keith’s call. Ronnie, however, I was left in no doubt, is the glue that holds it all together. He was always the social glue; he was hired, effectively, to give Keith a companion who’d keep up with him and then hold him back, as and when it was needed. But now, what with Keith’s arthritis, and his attached inability to play quite as solidly, or certainly as consistently, as he once could, it falls to Woody to hold this whole thing together. Keith still leads the band, as ever, but Ronnie circles him, musically and literally, and plays through everything. He is quite brilliant, and clearly, unlike in some previous tours, on the wagon – he couldn’t possibly perform like this if he was drinking.

On July 26th, in just over a week, Michael Philip Jagger will turn 70 years old. I want you to imagine what a normal 70 year old man is like. Perhaps he’ll be still working in a job he hates. He could be retired and filling his days with gardening or reading or going on a cruise perhaps. He might have a bit of middle-aged spread (as goodness knows a lot of the men in the audience did, and felt no compunction about showing off), or even an overflowing beer gut that clothing fails to tame. The once lustrous hair he had has started to thin or even made its escape completely. Then watch Jagger, howling it out, losing himself on harmonica, he never stops moving or working. And so, despite an undeniably wrinkly face, I cannot fail to marvel at what this particular pensioner puts in. He has a nice line in acting, all that mockney ‘Ar ya doin tonight Laandaahn!’ His voice, always a classic rock instrument, is in perfect nick, and just the sheer energy and approach of his performance is staggering. Morrissey always says he ‘appears’; he doesn’t perform. What he means is that he and his emotions are ‘real’ and his singing is from the soul, he’s not putting anything on. Mick is a performer in every sense. It’s so affected as to almost be cartoonish. He has always played this rock frontman character, which is a mile away from the cultured, yet bohemian, mischievous but whip-smart economist that he really is. What he does is a job. It’s a part he plays and my god, he plays it well. He prepares himself like a marathon runner, he trains and, on stage, he works his tiny little arse off. He runs miles and engages and communicates and it is his job to get the audience off, to never let the energy level drop. He’s one of the greatest and I felt lucky to have left it 18 years since I last saw him and for the performance to be better than it was then. Good genes (his dad was a PE teacher and both parents lived well into their 90s), hard bloody work and natural gifts make him what he is. It’s easy to take the piss, but you can’t watch him and be unimpressed. It’s impossible. I won’t go on about the songs because you’ll see the setlist below – it was all a highlight. Mick even found a smock dress to put on, in the same style as the one he wore for the ’69 show. And Ruby Tuesday (pardon my shaky, excited hand), played for the first time on this tour, took me back to 1990; I remember hearing it at Wembley so clearly. There were no low points, there was no filler (even new song Doom and Gloom sounds like classic Stones) and it made me want to see them again and again.

The whole experience was a magical blur and seemed to be over far too quickly. Nobody does this kind of thing better. Their songs are part of the fabric of this country and they have always been cooler and sexier than The Beatles ever were. The Beatles get you in the heart: the Stones aim somewhat lower. I’ve seen McCartney too and it is joyous, but not as passionate or visceral or real as it is watching the Stones. I couldn’t help think how happy mum would have been that I went to see her boys. She saw them in 1964 when she was 13. She took me to see them in 1990 when I was 13. And I saw plenty of kids the same age, whose grandparents are younger than the band, revelling in this extraordinary day, something they’ll be able to tell their grandkids about when we’re all gone. All except Keith of course, obviously. He’ll be around forever.

Start Me Up

It's Only Rock 'n' Roll (But I Like It)

Tumbling Dice

Emotional Rescue

Street Fighting Man

Ruby Tuesday

Doom and Gloom

Paint It Black

Honky Tonk Women

You Got the Silver

Happy

Miss You

Midnight Rambler

Gimme Shelter

Jumpin' Jack Flash

Sympathy for the Devil

Brown Sugar

Encore:

You Can't Always Get What You Want

(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction

...

Patti Smith :: Shepherd’s Bush Empire, London, 19-6-13

She has always had that same rumpled charm, since the beginning. I can’t think of any women in her profession who changed the visual aesthetic in popular music so greatly. Before her, you had 60s girl groups, Janis (not beautiful but certainly intending to exude sex), Joni, and of course the Debbie Harry’s of the world, and all that came after. People knew how to treat, and react to, beautiful women in music. They were either taken seriously ‘despite’ their looks or not taken seriously at all. You sang someone else’s songs, like Dusty, with glamour, or you wrote your own, like Joni, and both critics and the public did their best to fit you into a box. I watched an interview with Joni recently where she spoke candidly about the abuse she received in the early 70s for having the temerity, as a 21 year old, to write a song that went ‘I’ve looked at love from both sides now.’ How dare she, at that age, think she knows about such things in such depth? You can’t imagine that happening now. And it certainly didn’t happen to men – nobody had a go at Dylan for writing Masters Of War at 23 even though he’d never been further than New York and Minnesota.

So in 1975, this extraordinary woman appeared. With matted hair, wearing men’s clothes, she sang political songs and was certainly not what was accepted as beautiful. She didn’t play anyone else’s game. She wasn’t gamine or coquettish, she led a band of men, she had a gay boyfriend (Robert Mapplethorpe of course), and she had a song called Rock N Roll Nigger. People must have been horrified. She got called angry, because if women aren’t overly emotional or subservient (think of the women in Mad Men, and how Peggy and Joan are treated for not being obedient) they’re angry don’t you know, and she got called a man, and a hundred worse things. She might have arrived in the 70s but the reaction to her as a woman was very mid-60s. Now, she is accepted without question but back then she was treated as a threat. It was bad enough for Joni, and she was pretty and blonde.

You’d think all of this treatment would make her a bitter person, but that was absolutely not the woman who walked on stage last night. Your audience reflects you, understands you, and she knew it, she was grateful for it. She spent most of the show smiling, between songs, talking about how stupid she is, how she knows that striking poses is what’s expected of her, but can’t stop talking about silly things on stage. And then in the next second she’s talking about the usual protest singer stuff (fuck corporations, governments, capitalism etc), telling us we have to take our freedom, talking of violent protests in Istanbul and Brazil, spelling out P-U-S-S-Y R-I-OT in the style of G-L-O-R-I-A near the end of the show, to roars. She knows how to play the audience, how to create the show in her image, but she is tremendously charismatic, likeable and sincere.

This is a woman who, between the 17 years of 1979’s Wave and 1996’s Gone Again released one album, Dream Of Life, having basically given up her music career in large part to raise her two children. Another move that confounded the male-dominated corners of music theory who had painted her as a lesbian or a feminist, as if those things are all mutually exclusive and motherhood is incompatible with either. Her daughter, Jesse, joined her on stage, to play keyboards for the last third of the set, following bandleader Lenny Kaye’s three-song sojourn into Nuggets territory, with a nicely judged solo cameo, taking in covers by The Music Machine and Count Five . Incidentally, in the pantheon of albums about loss (Flaming Lips’ Soft Bulletin et al), her record Gone Again must be right up there. The acute concentration of the deaths of her husband, her brother Todd, her keyboardist Richard Sohl and Mapplethorpe was poured into the record, but rather than such pain being simply too hard to listen to, it’s comforting, relatable and empathic. She dedicated Because The Night, an inevitable highlight, to her late husband Fred ‘Sonic’ Smith, ‘the man it was written for’. There were plenty of other tributes too, with songs dedicated to and Johnny Smith and Amy Winehouse, the latter eulogised beautifully in This Is The Girl.

On stage, she is compelling, proselytising, and frankly, shamanistic. You’d follow her anywhere. I have friends in New York who have seen her play live repeatedly, and I never quite understood why until now. Her voice, a deep and powerful instrument, propels these songs of fight and hope to every corner of the venue. I was standing at the back, near the bar, where much conversation was taking place. After a few songs, people started shushing each other, during her between-song chats – something I have never seen in London at a concert. Gradually, the chatter lessened and the crowd stopped thinking about their drink orders or jobs or catching up with friends and focused their complete attention on the stage.

I’ve had a fair few live music experiences in my time. But I can honestly say that a life highlight was seeing the epic Horses/Gloria rendition at this concert. I can barely speak about it, the transformation of how I felt, the elevation, being utterly removed from the space I was standing in to feel transported to completely another place. Not just in the physical sense, where my mind fluttered to CBGBs and how it must have felt to stand in that shithole and hear the song for the first time. But also in the metaphysical sense, of being raised up off the ground. Like I said, only music does that so completely to me. It was an honour to be there, to be so consumed by a song I forgot where I was. The noise level after it was deafening, as she left the stage. The encore started with Banga, her most recent album’s title track and flew into the deceptively poppy People Have The Power. She led us on another treatise on being free, escaping governmental power and, even though you’d think a rich rock star telling us all to protest and find our joy in the world might be annoying or presumptuous or even ridiculous it just wasn’t, none of it was. Even a roomful of white people singing Rock and Roll Nigger didn’t feel bizarre or out of place, such was the power of the performer. The audience members were among the most varied at a rock concert I’d ever seen. There were people who must have jumped the Glasto fence in the 80s, old crusties, hippies, Red Wedge types, mums and dads, tattooed pin-up girls, students, hipsters, old punks, Guardian/Socialist Worker readers, people in suits who’d just left work, the age range going from fresh-eyed teenagers to desperate-to-escape wage slaves to baby boomers. Everyone listened, everyone heard, and everyone believed in the moment that we could all escape and take her advice, that we could be inspired to not put up with the social and economic conditions in which we live. Even if it was just for a moment, so what? It's better to lose yourself in it than to be a cynic, and it’s preferable to allow yourself that humanistic moment of naivety, of idealism.

It was a special night, a special connection, between two bodies of people. ‘You’re my fuckin’ show, thank you so much!’ That rare thing happened, the performer gave to us, we gave back, and the circle was complete.

Ask the Angels

Privilege (Set Me Free)

Break It Up

April Fool

Kimberly

This Is the Girl

Summertime Blues

Ain't It Strange

Beneath the Southern Cross

Talk Talk

Distant Fingers

Psychotic Reaction (Count Five cover)

Dancing Barefoot

Pissing in a River

Because the Night

Land

Horses/Gloria

Encore:

Banga

People Have the Power

Babelogue

Rock 'n' Roll Nigger

...

Neil Young & Crazy Horse :: Los Lobos :: The O2, London, 17-6-13

So, to Neil Young, and his inexplicably odd approach to an arena show. At the start of his classic concert movie, 1979’s Rust Never Sleeps, there’s a weird play going on, where men in Ewok-style hooded cloaks are constructing the stage and arguing with each other. This time, it was mad scientists, in white coats and big white wigs, all taking place to the soundtrack of A Day In The Life. The same props from that tour were also present – 20-foot microphone, outsized speaker stacks and flight cases and so on. And then suddenly, the entire band were stood on stage, in a row, hands on heart, as a Union Flag unfurled and God Save The Queen (he covered it on his album Americana) played. No fanfare, no big intro, he was just there, all in black, saluting the national anthem. Alright then. On went the fedora, followed by the battered Gibson, and we were off. It’s a beautiful guitar sound he makes, crunchy and precise yet distorted and savage, and the collective muscle memory of this band – Billy Talbot, Ralph Molina and Frank ‘Poncho’ Sampedro (who replaced original guitarist Danny Whitten) – forms a cocoon around him. They’ve played together, on and off, since 1969’s Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere. The first few songs went relatively normally, and then came Walk Like A Giant from his new record Psychedelic Pill.

It’s hard to say what audiences expect when they pay big bucks to see one of the so-called ‘heritage’ acts. But I’m fairly certain it wasn’t a 20-minute dirge, half of which was atonal feedback while pieces of paper blew across the stage. You could feel the collective disappointment that such a big portion of this show was being wasted by self-indulgence (or, if you want to pretend it’s interesting, and not pretentious, you can call it ‘a startling act of agitprop provocation’). However, in a sense, it’s entirely the crowd’s fault if they were disappointed. They should know better. I want you to imagine Mick Jagger as a quite adorable small dog. He jumps up repeatedly at the kitchen table, trying to get your attention, because he wants treats. So you make him perform for you a bit and reward him with love. He’s so keen, and he wants you to love him so desperately. Now think of Neil Young, and imagine a cat that just doesn’t give a fuck. He views you with disdain, accepts your food if you’re lucky, makes you work for affection, and buggers off out of the house if he’s bored with you.

This is the difference between someone who works hard to make you love him and someone who does exactly whatever the hell he wants and if you don’t like it that’s just tough. In a way, I just adore and hugely admire this approach. He plays his own game, and he doesn’t think about the audience at all for large parts of the show. Later on, he says ‘At times tonight, frankly, we sucked; but with what we do, that’s always a possibility’. He’s out there on a limb, and if the audience have come to hear Rockin’ In The Free World (which to be fair he does play sometimes) and half of Harvest, they’re in big trouble. He doesn’t care if there’s 200 or 20,000 people watching. He does what he does, and makes little concession, unlike pretty much all of his contemporaries. It's true that, in the current musical landscape, where getting people to shell out money is getting harder every day, live performance seems to have become more important than ever. So, what are we expecting when we pay for a gig, when the stakes are so high for the performer (though arguably, Neil is plenty rich and doesn’t actually need to do this to earn a living)? The wonderful Low recently played a gig that consisted of one song lasting 27 minutes and I’ll see Patti Smith, who’s had only had one hit record, this week. However, in the latter case, it’s a small venue, so there’s an unspoken agreement that you’re paying for proximity and the artist can do what they like. A normal musician, in the O2, would recognise that there’s 20,000 people present and tailor their setlist accordingly. But not Neil Young, not until a crowd-pleasing encore. In a way it’s maddening, but in another you just have to admire what he does, when faced with demands from a big audience. Almost every single song dribbles to an extended end, finishing with feedback and false endings. It’s almost funny, as you get kinda sorta tricked into applauding because you think it’s the end, only for the song to come back and drone on for another minute. And this from a man who has about 50 extraordinary songs to play you – instead, you sit there listening to walls of feedback for minutes on end. It’s crackers, let’s face it.

It’s not like he’s up there making no effort, he’s completely lost in the moment with his band, huddled together in the centre of the stage. He wrings every note out with utter conviction and passion. But it has its trying moments. I personally don’t get hung up in setlists, and I know enough about Neil to have expected some of the madness that met me, but even I had my patience tested. It’s a high-wire act; sometimes it works, now and then it doesn’t, but you have to appreciate the stubborn approach. After the interminable Walk Like A Giant wall of noise ended, he embarked on a trio of acoustic songs – which were utterly beautiful, and you’re even more baffled, being swung this way and that. First up, Red Sun from 2000’s Silver & Gold, then the gorgeous Comes A Time and then… Blowin’ In The Wind. It sounded beautiful, moving, and better than Bob could ever do it now. A piano-led new song followed (accompanied by another piece of theatrical eccentricity: a young woman, guitar case in hand, wandering about the stage before disappearing) and then it was back to the main show, though I could have stood for a longer acoustic section, such was its beauty. His voice, incredibly, seems untouched by decades of touring and held out its lovely high tone throughout. Then, the energy level rose, with Cinnamon Girl, but dropped on a 15-minute version of Fuckin’ Up – which was mildly funny, getting the crowd to repeat one profane line over and over, but wore thin, again (though it was amusing to see the insipid corporate hell of the O2 subjected to such a venture). My head was spinning, and then came a lovely surprise, a classic track, Mr Soul, by his old band Buffalo Springfield. A song that lasted less than 5 minutes too, how novel. He then fancied a little chat with the audience, which was just so heartfelt and charming, and started with the bit about the band sucking, and took in a whole heap of gratitude, that he understood people had to leave because it was getting late, then particularly thanked parents with little ones for coming and that he hoped they were in bed without a care in the world by now. This was followed by a massive, crunching, monstrous version of Hey Hey My My. This is a song that will be played in 100 years, a song that can never get old. The place roared its approval and then it was over, and people started making their way to the Tube. What a bizarre, brilliant and crazy show.

But then, he bounced back onto the stage, this man of 67, who was hours from death to a brain aneurysm only 8 years ago, and ripped into one of the best encores I’ve ever heard, as people danced in the aisles. First, Like a Hurricane. Second, from one of his best ever albums Tonight’s The Night, Roll Another Number For The Road, and then just one more, as we flew past the 11pm curfew: Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, truly one of his best songs, to end the night. It was worth the fine he’ll have to pay (he told his management to get out their calculators). It was baffling and wonderful, maddening and affirming, unexpected and expected. He’s a crazy old bastard, but he does it all exactly how he wants it, with few allowances. How many others can say that? At his first gig in Newcastle, last week, he took on an interloper: "Sing like you mean it?" he rounds on a heckler. "What the fuck would you sing for if you don't mean it?". Exactly.

Love and Only Love

Powderfinger

Psychedelic Pill

Walk Like a Giant

Hole in the Sky

Red Sun

Comes a Time

Blowin' in the Wind

Singer Without a Song

Ramada Inn

Cinnamon Girl

Fuckin' Up

Mr. Soul

Hey Hey, My My

Like a Hurricane

Roll Another Number (For the Road)

Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere

...